On Saturday, December 9th, in front of a packed crowd at BMO Field, Toronto FC defeated the Seattle Sounders 2-0 to win the 2017 MLS Cup. Their win was decisive; they dominated the possession, defended well, controlled the rhythm of the game, created more scoring opportunities and capitalized on enough of them to ensure victory.

In the week that has passed since this historic win, the city of Toronto has been abuzz with support for their Football Club. It has been evident and visible in person across the city, as well as all over social media.

A question that must be asked amid all this success, however, is when – or even if – it will ever translate into improvement in the performance of the Canadian National Men’s Soccer Team.

With popularity of soccer in Toronto and Canada at an all-time high, our Men’s National Team still toils in obscurity; at the time of the writing of this article, we are ranked 94th in the world, behind countries like Gabon, Belarus and Armenia.

The United States has seen a similar surge in the popularity of soccer in the 23 years since their hosting of the FIFA World Cup in 1994 and subsequent inception of Major League soccer the following year, and yet, they too have had a recent drop in the performance of their Men’s National Team, having failed to qualify for the World Cup for the first time since 1986.

Just what is it about Canadian and American soccer that has led to these poor results internationally? And what – if anything – can be done to capitalize on the popularity of Major League Soccer for the Canadian and United States Men’s National Teams to perform better in the future?

In this 3-Part article, I will provide my 3 suggestions, beginning with Part 1 below.

Part 1: Institute and limit of the number of foreign players allowed to play in Major League Soccer.

In other words, incentivise clubs to prioritise domestic players over foreign ones. This has been an interesting and hotly debated topic ever since the infamous “Bosman Ruling” – so named after Belgian professional Jean Marc Bosman went to the Belgian Civil Court to challenge his Belgian club, Standard Liege, when they attempted to prevent his move to the French League 1, on the grounds that this decision was a violation of the “freedom of movement between member states” tenet of the Treaty of Rome, signed during the creation of the European Community – in the mid-1990’s.

Essentially, the Bosman ruling ushered in an era of player movement across all the top European professional leagues, because it added “football” – previously recognized as a “sporting consideration” and thus not applicable to the guidelines of the Treaty of Rome – to the list of “employment considerations”, and thus it became seen as unlawful and discriminatory for European professional soccer clubs to restrict the movement of soccer players based on their nationality.

From 1995 onward, all European leagues – not wanting to be seen as discriminatory and afraid of fines and sanctions – eradicated their quotas on the number of foreign players, and the results were that top leagues and top clubs who could afford to import foreign talent, did so at will.

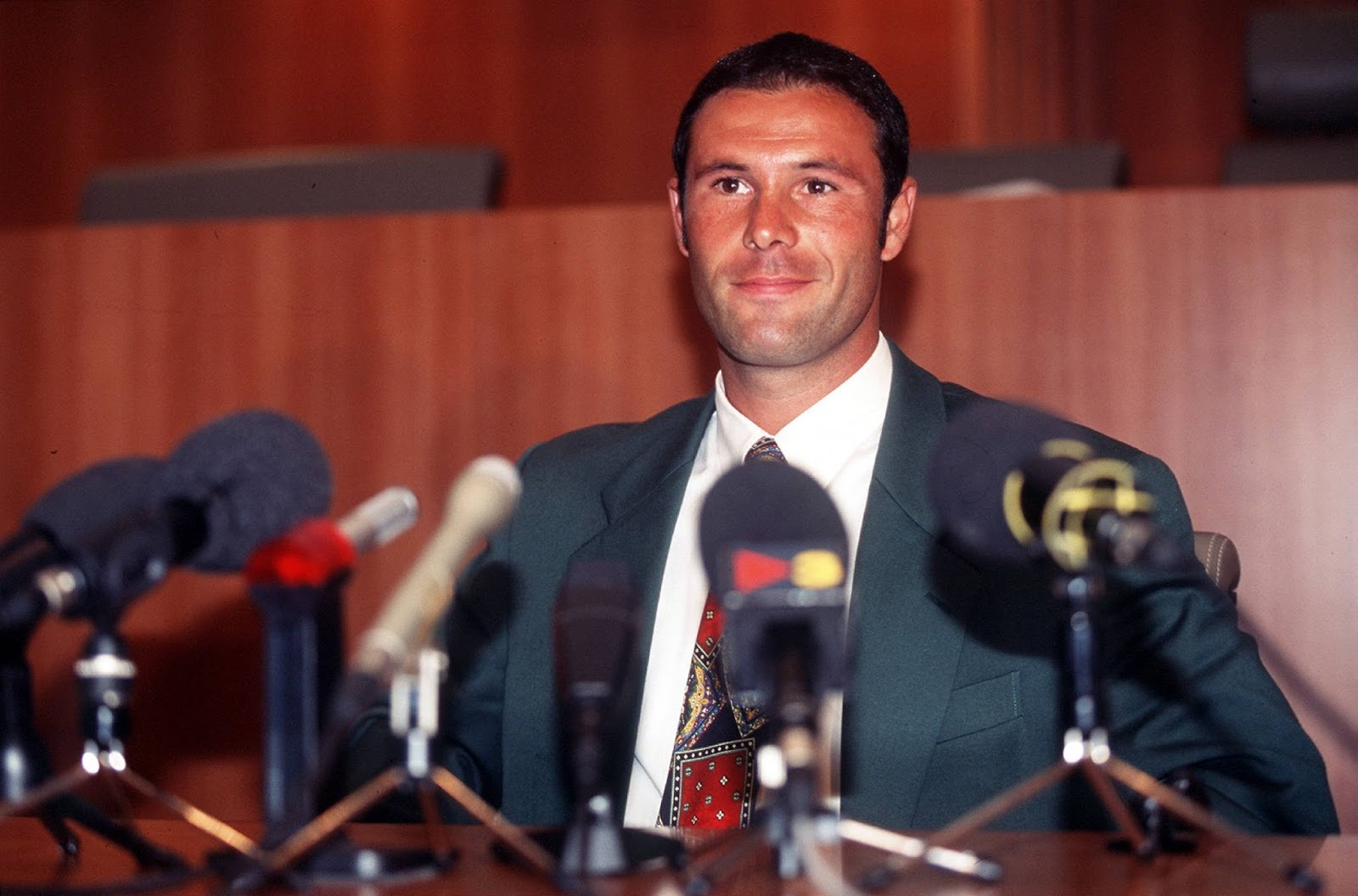

Belgian professional soccer player Jean-Marc Bosman, during his court proceedings in 1995

The influx of foreign players into top European leagues has been of particular concern in England and Italy, two countries who have both seen a relative decline in the development of their domestic players and subsequently, in the performance of their Men’s National Teams, since the time of the Bosman Ruling. In England, prior to the Bosman Ruling, the percentage of foreign players in the English Premier League totaled 20%; this number has risen to 69.2% – higher than any other professional league in the world – as of 2017.

The English failed to qualify for the World Cup in 1994 and have had a string of poor performances at major tournaments since that time, including failing to qualify for the 2008 UEFA European Championship in Poland and Ukraine; failure to progress past the group stage at the most recent World Cup in Brazil in 2014, and losing in the Round of 16 to minnows Iceland at the 2016 UEFA European Championship in France.

In Italy, a decline in performance of the Men’s National Team following the influx of foreign players arrived more slowly, but it arrived nonetheless. Italy’s Serie A ranks 5th among professional leagues in percentage of foreign players, with 55.5%. While the Italian Men’s National Team did have some great international performances in the 2000’s, culminating with winning the 2006 World Cup in Germany, they have failed to progress past the group stage in the two World Cups since then and, most recently, failed to qualify for the 2018 World Cup in Russia, the first time they have done so in 60 years.

For Canada and the United States – both countries which have not had a sustainable professional soccer league prior to the inception of Major League Soccer, and both also countries in which soccer is not the most popular sport – the lack of restrictions on the number of foreign players seems to have been even more impactful.

Major League Soccer has a total of 49% of its total players coming from foreign countries, and Canadian club Toronto FC, the current MLS champion and the best team in the league over the past two seasons, employs just 4 Canadians – 14% of their total of 28 players. Even 25% of TFC II – Toronto’s USL team – hail from countries outside of Canada.

And of course, it bears mentioning again that, despite the recent surge in popularity of Major League Soccer in the United States in general, and of Toronto FC in Canada specifically, both the United States and Canadian Men’s National Teams have not been able to capitalise on this success in terms of improved performance in international competitions.

Whether the relationship between the high number of foreign players in MLS or other aforementioned European leagues like the English Premier League or the Italian Serie A, and the subsequent poor performances by these countries’ national teams, is based simply on correlation, rather than causation, is another matter.

Proponents of allowing foreign players into domestic leagues point to the increased challenge that domestic players face for starting spots and playing time as a positive factor that will contribute to their overall development and mental toughness; detractors argue that by not giving domestic players a fair chance, they end up languishing on the bench or with weaker teams and thus suffer developmentally.

In this author’s opinion, if American MLS teams instituted a quota or rule limiting the maximum number of non-American born players, and Canadian MLS teams did the same with non-Canadian born players, eventually the development of young American and Canadian talent would improve and thus, the performance of the American and Canadian Men’s National Teams would too.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of this 3-Part article next weekend, and please feel free to share thoughts and feedback prior to!

Leave A Comment