Over the past 10 months, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected nearly everyone in the world, from children to the elderly, public sector employees to private business owners, and of course, front-line health care workers and medical staff.

Sports have endured large-scale shut-downs, cancellations, postponements of athletic training and competition, at both the amateur and professional levels, and everything in between.

Of course, over the Summer and Fall months, many amateur and professional sports teams and leagues around the world began to re-open, giving a much-needed boost of positivity during an increasingly negative and frustrating time.

Athletes at all levels of sport began to train and compete again and, unfortunately – despite the best efforts of medical and athletic therapy staff, owners, organizers and administrators – many of them contracted COVID in the process.

What are the acute and chronic consequences of COVID-19 in athletes? What does the science say about short- and long-term recovery and return-to-play? And how can athletes optimize their training and recovery post-exposure?

While the Coronavirus seems to be affecting different populations – including athletic populations – in slightly different ways, two primary areas of concern have emerged in recent medical research: chronic respiratory illness and cardiac remodeling.

Respiratory Illness

The first is the broad topic of the potential for chronic respiratory illness – that is shortness of breath, inflammation of the airway, and risk of respiratory infections including bronchitis and pneumonia – in athletes returning to train following recovery from the COVID-19 virus. The virus has been shown to lead to the development of lower respiratory tract infections in patients, including young people and athletes (Hull et al., 2020).

As is the case with the general population at large, athletes who contract the virus are also typically required to quarantine and self-isolate for a period of 10-14 days, and during this time, they will likely not participate in any high-intensity training.

If any acute symptoms of respiratory illness are not present following the 10-14 day time period, the medical consensus is that athletes may return to training, following some of the guidelines described in the following paragraphs. If symptoms persist, however, and the athletes appear to have been chronically affected by the virus, athletes must remain under the guidance and care of their physicians. They typically will be required to rest for longer periods of time until they are symptom free (Hull et al., 2020).

Unfortunately, this lack of high-intensity training over 1-2 weeks will very likely lead to de-training, in which an athlete’s aerobic fitness levels can significantly decrease.

Luckily, according to recent research, athletes who have fully recovered can pick up where they left off (prior to getting any respiratory infection, including COVID), as long as their training load is well managed and there is not a significant increase in training load (Campbell and Turner, Frontiers in Immunology, 2018).

What does this mean for the average athlete or coach?

Once an athlete has recovered from COVID-19 and has been medically cleared to participate in exercise, their training load – that is, the volume and intensity of their training, must be planned with small, incremental increases from one week to the next, and close monitoring must be done both of the external load (amount of time, number of repetitions of exercises, etc.) as well as the athlete’s physiological responses to the load (heart rate, Rating of Perceived Exertion, etc.).

Given the fact that a 10-14-day period of inactivity is very similar to the amount of time off athletes might have from other training- and game-related injuries (for example, ligament sprains or muscle strains), the same initial reductions and incremental increases in training load used when recovering from other injuries with similar time periods of inactivity may be used.

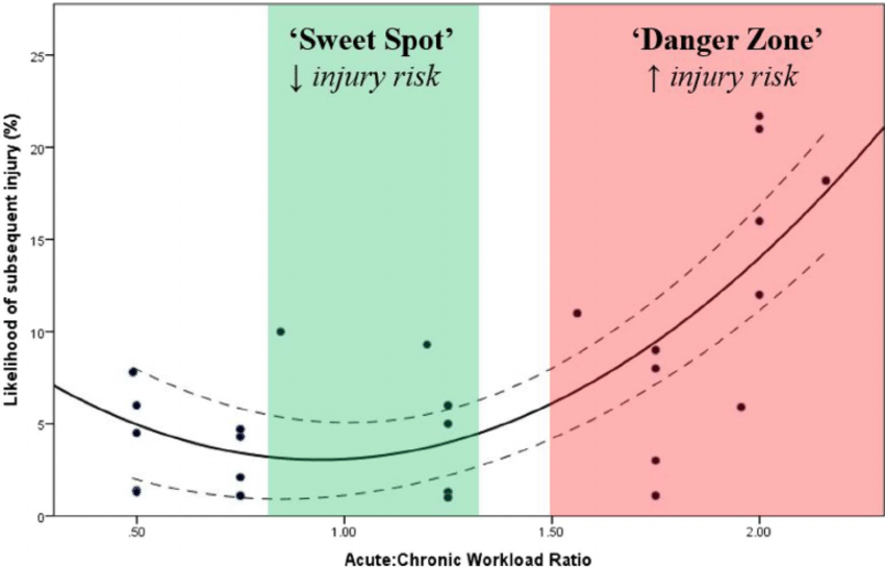

A simple way for coaches and fitness coaches working with athletes recovering from COVID-19 to determine how best to manage training load is to use the “Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio” (ACWR). The ACUTE workload is training load on a given day – that is, today. The CHRONIC workload is the average training load over a specified period of time, usually 2-3 weeks.

Figure 1: Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio

To help explain this concept a bit better, have a look at Figure 1 (from a paper by Gabbett, 2016). The ACWR must be kept between 0.8:1 and 1.3:1 in order for most reduced risk of injury. That is, the daily workload must not be more than 30% higher than the chronic workload, otherwise the risk of injury is significantly increased. If it is less than 20% of the chronic workload, then the athlete’s fitness does not improve.

For more information about exactly how to plan, calculate, monitor, track and manage training load, check out the links to my previous article and videos about this topic.

Cardiac Remodeling

A second – and more pressing – concern among medical professionals regarding return-to-play in athletes recovering from COVID-19, are the long-term cardiopulmonary re-modelling. In other words, COVID-19 can make changes to the structure of the heart and lungs in some individuals.

According to a Medical Consensus Statement published in the October 2020 issue of Cardiovascular Imaging, COVID-19 may cause sub-clinical cardiac problems, including myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle); pericarditis (inflammation of the pericardial sack that contains the heart and blood vessels); and right ventricular dysfunction (abnormalities in the function of the right ventricle of the heart, which pumps blood into the lungs) in the absence of significant clinical symptoms.

Interestingly, this article also notes that the re-modelling of the heart following intense exercise in athletes – that is, the enlargement of the heart muscle, and mild abnormality of systolic heart function that occurs through regular endurance training – can be misdiagnosed by physicians as COVID-19 related cardiac injury.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (“CMR”) imaging can help physicians to identify whether any heart remodeling seen has occurred as a result of regular, strenuous aerobic exercise or due to the COVID-19 virus in recovering athletes.

So, if athletes contract COVID-19 and are still experiencing symptoms beyond the 10-14 day quarantine and self-isolation time period, having them undergo CMR imaging can be a way for physicians to screen for potential long-term heart problems and determine whether or not it may be safe for them to return to training and competition (Phelan et al., 2020).

Unfortunately, because it is such a new disease, no long-term studies have been conducted yet that can determine exactly what the best practices are for athletes when it comes to return-to-play following contraction of COVID-19, but these guidelines are a good place to start:

- If athletes recovering from COVID-19 do not show abnormal findings from CMR imaging following 10-14 days of quarantine, they may return to training with modifications and decreases in training load.

- Specifically, plan, monitor and adjust the Acute: Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR) and keep it within the 0.8-1.3 range, to minimize the risk of injury in return-to-train protocols.

- If abnormal findings are reported from CMR imaging, limiting strenuous exercise for a period of 3-6 months should allow enough time for inflammation to resolve, and when it does, return-to-play would then depend on the normalization of these abnormal findings.

References

Campbell, J. P. & Turner, J.E. (2018). Debunking the Myth of Exercise-Induced Immune Suppression: Redefining the Impact of Exercise on Immunological Health Across the Lifespan. Frontiers in Immunology, 9: 1664-1324.

Gabbett TJ. (2016). The training—injury prevention paradox: should players be training smarter and harder?, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(5): 273–280.

Hull, J.H., Loosemore, M., Schwellnus, M. (2020). Respiratory health in athletes: facing the COVID-19 challenge. The Lancet, Respiratory Medicine Spotlight, 8 (6): 557-558.

Phelan, D., Kim, J.H., Elliott, M.D., Wasfy, M.W., Cremer, P., Johri, A.M., Emery, M., Sengupta, P.P., Sharma, S., Martinez, M.W., La Gerche, A. (2020). Screening of Potential Cardiac Involvement in Competitive Athletes Recovering from COVID-19: An Expert Consensus Statement. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging, ISSN 1936-878X.